"In Defense of Facsimiles"

by Alexander Silbiger

Reprinted with permission from Historical Performance Vol. 7, No.2, Fall 1994

of Early Music America. Copyright, Early Music America, Inc.

I was pleased to see an article on facsimiles by Ronald Broude of Broude Brothers, the publishing house that played a pioneering role in producing fine reprints of musical monuments ("Facsimiles and Historical Performance: Promises and Pitfalls," [Historical Performance, Spring 1990, pp. 19-22]). For years I had admired and treasured these beautiful examples of the art of bookmaking, but my pleasure turned to distress when I learned of the promises that might have been broken and the pitfalls fallen into when carrying the volumes from bookshelf to music rack. Some of Dr. Broude's reservations about performing directly from facsimiles were right on target, but his overall discouraging attitude towards that practice reminds me of those who used to reject performance on historical instruments because it was often done badly. (There is of course a close connection between the early instrument movement and the growing interest in performing from facsimiles.) We now expect performances that are competent and artistically inspired as well as historically responsible. Why not search for good facsimiles and, when available, make those our preference for performance?

By "good" facsimiles I mean those that are a pleasure to read, but not necessarily those that reliably communicate the intention of the composer. Our pleasure will depend not only on the clarity and attractiveness of what we see on the page but also on our ability to manage the notation without great effort. Such ability will of course depend on a reader's experience. Some keyboard players never venture beyond standard treble and bass clefs; others readily accept soprano or alto clef, but draw the line at baritone or mezzo-soprano clef, or at eight-line staves, or at German tablature, or whatever. However, with only a little experience much music in facsimile becomes quite accessible, and among it is some of the very best: almost all French keyboard prints and manuscripts from Chambonnières to Rameau, much of the French chamber repertory of Marais, Couperin, and their contemporaries, the Frescobaldi intavolatura editions, the Froberger autographs, Bach's Clavierübung as well as some of his autographs, most prints and manuscripts of Scarlatti's sonatas—in short, most editions printed from engraved plates, dedication manuscripts, and other fine handwritten copies. More difficult to manage are early English virginal sources (because of frequent gross misalignment of voices), editions set in movable type (some are better than others), and messy, hastily copied manuscript books; also German and Spanish tablatures, which often remain codes impossible to crack at sight. Thus it comes as no surprise that the first group corresponds to the most popular types of facsimile reprints.

When contemplating the issue of facsimiles vs. modem editions, it is wise to consider precisely in what way they differ. The modem edition aims to provide a text that would lead to a performance of a piece closely approximating its conception by the composer. Editors try to achieve this goal—in the ideal case—by carefully examining all early copies of the piece, and by establishing their text according to procedures for which they received special professional training (often by years of academic study). The facsimile, on the other hand, reprints a text that represents just a single one of the sources an editor would have used; thus it would seem to provide a much more limited and possibly flawed view of the composer's intention. But we must not lose sight of the fact that the facsimile text is a text that a musician contemporary to the composer might have performed from—with or without the composer's sanction—while the modern edited text is not.

Underneath the whole idea of the critical edition is the notion of an ideal text that represents the composer's intention and that is at least approximately recoverable by an analysis of the sources. This time-honored editorial procedure had its origin in scriptural scholarship, which set as its goal the reconstruction of the "true" text of the Bible (reflecting the Divine intention) from the many divergent and possibly corrupt versions scattered over the earth. This procedure was subsequently applied to the preparation of editions of the canon of works of classical authors and, in music, to the reconstruction of the authentic, eighth-century "Gregorian" version of plainchant.

There are problems with transplanting the notion of an "ideal text" to much of our early music repertory (there are, in fact, problems with applying it to the texts for which it was devised—but that is not the concern here). Do the different sources of, say, some little dance piece present more or less corrupt versions of an ideal conception of that piece in the composer's mind? Or do they show us merely how that composer played it or thought of it one day (on another day thinking of it differently or only half remembering it)? Or how a colleague or pupil, perhaps just as fine a musician, thought of it?

Actually, for a surprisingly large segment of this repertory we possess only a single manuscript copy or single exemplar of a printed edition (and we should be grateful that by some good fortune it survived). The question becomes moot; the accident of history has removed one of the main reasons for preparing a critical edition. When we possess more copies, but these are merely reprints with corrections—Broude gave the example of the numerous successive printings between 1680 and 1720 of Book One of Marais' Pièces de Violes—why not publish a reproduction of the last version, which presumably incorporates the most exhaustive set of corrections? This assumes the changes are indeed corrections and not artistic changes of mind by the composer (or, God forbid, tampering by another party). Broude does not tell us in which category Marais' 400 changes fall,[1] but if they represent compositional changes of mind, are we sure that we would prefer Marais1720 to Marais1680? And why should we, as performers, trust some editor to make this decision for us—since the decision may ultimately be a matter of personal taste? One might respond that a critical edition, unlike a facsimile, provides all variant readings in its "Bericht," and hence leaves the performer that choice. But do I really want to perform a piece with one measure chosen from Marais1680 and the next from Marais1720?[2] Or would it be more sensible to play the version representing Marais1680 (or Marais1720 as the case may be), correcting actual errors as needed?

There is another reason why the concept of the critical edition does not transfer well from literature to music. Literary texts are encoded as a string of distinct symbols—letters and punctuation marks—that can take on a great variety of handwritten and printed shapes without affecting the message communicated by the text. Some purists might argue for the preservation of original spellings, but not for the preservation of the original calligraphic styles or fonts, to which generally no semantic significance is attached. The communication of a musical text depends on a much more complex two-dimensional graphic representation, and while a musician's response might not be affected by, say, substituting round for diamond-shaped noteheads, it is likely to be affected by beaming, direction of stems, transformation of note values, horizontal and vertical spacing and other aspects of layout—even when in theory such changes are not supposed to make a difference. As music engravers and, more recently, designers of computer music printing software have discovered, performers are extremely sensitive to the precise appearance of music on the page. Thus, even an edition that renders correctly every pitch and duration still may not communicate all the information of the original. Some of that information may be contained in calligraphic gestures, to which a performer may respond with analogous musical gestures, for example a forward surge or sudden holding back. To put it in hi-tech terms: literary texts are encoded purely in digital format, but in musical texts there is both a digital and an analog component. The latter component tends to be distorted if not suppressed in modern editions.[3] Sometimes this analog component was introduced deliberately, as in the free preludes of the French clavecinistes, or Forqueray's sarabande La Léon, which is accompanied by the instruction: "To play this piece in the manner I would wish that it were played, one must pay attention to the manner in which it is written; the treble appears almost never right above the bass" (see Figure 1). Beyond that, the aspect of the original score may convey something less tangible of the style or spirit of the age: one need but compare the graceful and organic appearance of a seventeenth-century engraving with the machine-like regularity of an edition from our own time.

Figure 1: From Pièces de viole composées par M. Forqueray le père,

mise en pièces de clavecin par M. Forqueray le fils (1747).

mise en pièces de clavecin par M. Forqueray le fils (1747).

Broude presents a further argument that some publications of music were in fact not intended to be played from, but rather to serve "archival purposes." It is indeed conceivable that some early music books served as repertoire depositories, from which copies could be prepared for practical use, while others may have been prepared for wealthy collectors, who had no intention of playing from such "musical coffee-table books." However, there are plenty of indications that the seventeenth- and eighteenth-century publications most attractive to performers today did not fall into those categories, for example the frequently evident concern to avoid awkward page-turns. Broude suggests that Forqueray's Pieces de viole could not possibly have been sight-read from the original edition because it is so densely engraved, but this is hardly a typical example. It is difficult to imagine anyone sight-reading that music, no matter what the format of the publication (neither does one encounter many pianists sight-reading Liszt's virtuoso works in public), but professional viol players of our time usually are quite comfortable performing from facsimiles of Marais' Pieces de viole.[4] To be sure, most surviving copies of early music were probably never or rarely played from, since they likely owe their survival to having remained in the libraries and archives of noble families rather than having circulated among musicians, but certainly in the case of prints the archival copies would not have looked different from the copies that were in practical use. As to editions being too small for comfortable reading—Broude mentions the Petrucci partbooks—I would hate to draw conclusions on that basis, having often seen musicians (especially continue players) read from miniature pocket scores.

Broude suggests that the elaborate ornamentation provided in editions such as the Chambonnières Pièces de clavecin (1670) were not really intended for professional performers but for amateurs not capable of improvising their own embellishments, and that observing those ornaments literally might cause one's performance to lack spontaneity. François Couperin would not have agreed with him, since in the preface to his Troisieme livre de pièces de clavecin he expresses his annoyance at hearing people ignoring his written ornaments after all the trouble he took in marking them in his pieces and explaining them clearly in his L'art de toucher le clavecin. He considers this inexcusable, since there is nothing arbitrary about their placement, and he concludes, removing any remaining doubt on this matter, "I declare thus that my pieces must be performed as I have marked them, and that they will never make the proper impression on persons with true taste unless one observes to the letter (à la lettre) everything I have marked without either additions or deletions." Or as Johann Kaspar Kerll puts it in the preface to his Modulatio Organica (1686) with more brevity and wit: "I wish here to admonish organists not to subject [my] themes to their own whims, manipulating them as they please: well-cooked food is bad when cooked a second time."

Broude observes that some of the Chambonnières pieces exist in less elaborate versions in manuscripts from the composer's circle; in fact, printed compositions by several other composers also survive in manuscript versions that are more sketchy in comparison, or have fewer embellishments (e.g., Caccini's songs, d'Anglebert harpsichord pieces). I believe the likely explanation to be, however, that the manuscript versions were prepared by and for people in the composer's immediate environment, where details of the intended performance practice would be communicated by example or would be well enough known. When, on the other hand, something was sent into the world by the distribution of hundreds of printed copies, the composer would have little control over its performance, and thus felt a greater need to communicate his intentions with some precision. This concern was also expressed in the common reason given by so many composers for publishing their music: the numerous corrupt copies that were circulating in manuscript and that distorted their creator's ideas; this surely is prima facie evidence that composers were concerned with the correct realization of their intentions (notwithstanding claims to the contrary by some scholars today). With Froberger this fear apparently was so great that he asked his patroness not to give copies of his compositions to anyone else, since without his mediation they were likely to butcher them.[5] Clearly these composers did not believe that once they had completed a composition they should relinquish all claims to authority over the work and that it should become fair game for the unbridled artistic interpretation of any performer.

If composers were worried about how distant contemporaries might ornament their music, one wonders how they would have felt about musicians attempting to recook them several centuries later for the sake of "spontaneity." Pianists don't seem to feel the need to substitute their own ornaments for the ravishing embellishments in Chopin's nocturnes, even though we know that he often changed them himself in performance. His expressive and highly individual musical lines (or those of Mozart, or Bach, or Frescobaldi) are nothing but written-out ornamentation. Indeed, as Schenker has taught us, if you strip away all ornamentation from any tonal piece, you are left with "Three Blind Mice." But if anyone thinks they can improve on Chopin or Bach (or on Couperin or Chambonnières), more power to them!

Of course, for musicologists who wish to study ensemble music that survives only in separate parts, the preparation of score editions is essential. Similarly, someone directing a work for large instrumental and/or vocal forces will probably need to have a score made, if none survives (often it does). But I'm not so convinced that a competent continuo player is always better off reading from a score than from an original figured bass part. My own experience is that one listens more carefully and integrates better in an ensemble—that is, functions less as an "accompanist" (or coach/accompanist) in the modern sense—when reading from such a part. Clearly the character of one's continuo realization will be different when one responds to what one hears other instruments do than when one manufactures the part on the basis of one's reading and analysis of the full score.

But the main question is this: Why should we assume a priori that any score prepared some centuries ago by one musician for another musician to play from cannot be used by a musician today without the intervention of someone (often a non-musician) with a PhD in musicology? Why does the score first have to be entirely rewritten in some other form and accompanied by a lengthy critical report that can only be understood by someone else with a PhD in musicology? Unfamiliar notational conventions can usually be mastered with some practice, and notational problems often are more successfully solved by a musical intuition educated by experience with the repertory (and by some willingness to experiment) than by theoretical analysis. In principle editors could of course be useful for finding and correcting mistakes, but in this respect their track record is not good. While I have no statistics to back this up, my overall impression is that in all too many modern editions the number of new mistakes introduced by the editors exceeds by far the number of old ones they catch and correct. This is not necessarily because modern editors are sloppier proofreaders, but rather because so many appear to lack the musical training and experience that would alert them at once that a given passage is impossible as it stands, regardless of style, period, or originality of the composer. The accuracy of old prints and manuscripts varies widely, but there are many (particularly among the ones most attractive in other respects) that were prepared with exceptional care, and I'm afraid that the chances are generally much greater that a modern editor will mess them up than that he will improve them. Indeed the reason many performers have come to distrust modern editions is not, as Dr. Broude suggests, because of the addition of interpretive markings (which in early music are becoming increasingly rare) but because, notwithstanding scholarly pretensions and claims of Urtext, they have often proven unreliable and error-ridden.

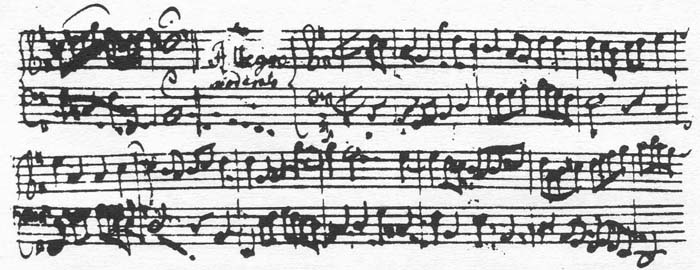

I think the potential of "edited facsimiles" Broude describes is attractive, although dangers lurk in such doctored facsimiles. Indeed dangers lurk even in the removal of "random ink-spots, dead insects" and other blemishes—procedures that Broude regards as essential to good facsimile publishing, along with the preservation of faint or imperfectly inked small ornaments, accidentals, and continuo figures (and one might add, bowing and fingering marks, often of even more tenuous appearance). But one editor's dead insect may be another editor's double-shake-and-relish; I remember a debate on one of those little critters that appears in a Bach autograph and was interpreted by most editors as an ornament even though its location makes little sense (see Figure 2; at issue is an appoggiatura to the second of two tied notes in m. 7 of the Allegro moderate).

Figure 2: From J.S. Bach, Sonata No. 1 for Viola da gamba and Cembalo (BWV 1027),

mvt. 4 (autograph keyboard part). Berlin, Deutsche Staatsbibliothek, Mus. ms. Bach 226.

I am not proposing that we do away with critical editions. For many works of composers like Bach, the source transmission is very complex, requiring sophisticated scholarly analysis, and because of the special status of those works in our musical culture there will probably remain a desire to establish some sort of canonical text, accompanied by a full account of surviving variant readings. At the same time there is still a place for "performing" editions aimed at non-specialist musicians. Indeed, one might welcome the return of pedagogical editions of the kind now out of favor, in which experienced and knowledgeable performers present their versions of pieces from the early music repertory accompanied by interpretive markings, articulation signs, fingerings and bowings, and whatever else is needed for a satisfactory performance. While we rightfully reject such editions when the works are interpreted within the framework of nineteenth-century taste and instrumental techniques, perhaps we should not reject them when they are prepared according to current notions of appropriate performance practice (even if this inevitably would mean that those interpretations represent late twentieth-century taste, or in any case late twentieth-century notions of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century taste).

Broude concludes by envisioning a future in which performers will return to performing from modem editions. My own utopian version is more or less the mirror image of his: one in which musicians will generally play from high-quality facsimiles but in which for works under serious study they will consult available critical editions. In the real world I expect musicians to continue using a great variety of types of editions, from pure untouched reproductions to doctored or edited facsimiles, critical “scholarly” editions, and heavily edited performance editions, with their choice depending on the nature of the music, the clarity and legibility of the source, and the skills and preferences of the performers. I can only hope that publishers will continue to make such options available to the musical world.

Alexander Silbiger teaches in the Department of Music at Duke University. He was General Editor of a 28-volume facsimile set, 17th-Century Keyboard Music, for Garland Press, and prepared critical editions of works by Matthias Weckmann and Nicola Vicentino.

[1] 1. In fact, almost all of the 400 changes (spread over ninety-three pieces) appear to be additions of ornaments, fingerings, bowing, etc., rather than compositional changes of mind.

[2] 2. Sometimes the answer might indeed be yes: Froberger's autographs generally offer the most accurate texts for his works, but there are other sources, e.g. the so-called Bauyn MS, that can be shown to incorporate the composer's later revisions of certain passages from the autographs, even if overall their texts are clearly less reliable (see this author's "Tracing the Contents of Froberger's Lost Autographs," Current Musicology 54 [1993]: 5-23). Thus a performer might in fact like to modify the autograph text accordingly. However, modern editors have not presented such a modified text, probably because they feel that the existence of the autograph has relieved them of further editorial decision-making.

[3] 3. A fuller consideration of this point, with specific examples, can be found in a review-essay on early keyboard editions by this author in the Journal of the American Musicological Society 42 (1989): 183-84.

[4] 4. They might, in fact, be less comfortable with the massive bulk of the modern Broude edition, which has probably caused more than one music stand to topple over, although they surely will want at the very least to have this magnificent edition by John Hsu—an exemplary model of editorial scholarship—available for consultation.

[5] 5. "[Froberger] often had said to me that many did as if his compositions were theirs, and did not know what to do with them, but only spoilt them," as quoted in Gustav Leonhardt, "Johann Jacob Froberger and his Music," L'Organo 6 (1968): 33.