|

| Select Music Facsimiles from Italy by Ardal Powell Reprinted with permission from Traverso, Vol. 11, No.3, July 1999. Copyright, Folkers & Powell, Makers of Historical Flutes |

To enable everyone to form an independent basis for interpretation" —that, according to Frans Vester, is the most important task a musical edition has to perform. Vester, who was not only the preeminent Dutch flute virtuoso and teacher of his generation, but also a tireless and thoughtful editor and researcher himself, decried musical texts that modern editors had "revised", "improved", or "otherwise mutilated". He protested that "a bad edition, when unavoidable for lack of a better one, is not only useless but insulting", since "the editor apparently considers us [musicians] incapable of arriving at our own interpretation". In place of such confections Vester argued in favor of an "ideal edition" (the scare quotes are his own), the work of careful editors who knew their historical sources, printed in modern type rather than the less familiar facsimile form. For Vester, the goal of such work was to strip away generations of accretion and error, to produce an Urtext, a "correct edition, one which reproduces the text as it was originally handed down". Vester laid out these ideas in a 1984 essay on "Publishers, Editors, Editions and Urtexts" (ed. Rien de Reede, Concerning the Flute, Amsterdam: Broekmans & Van Poppel, 1984, 121-28). But already by that date the objections Vester had raised to facsimile editions—that the continuo parts were unrealized, the typefaces hard to read, and the clefs sometimes unfamiliar—had begun to seem like minor inconveniences well worth spending a few hours’ practice to overcome. The payback of reading baroque and classical music from facsimiles, performers soon learned, was that the text conveyed precisely the degree of information contemporary musicians needed to make a convincing intepretation—no more and no less. If the text lacked editorial hints on performance, that only encouraged us to search for appropriate directions in contemporary tutors. If it contained mistakes, there was nothing for it but to think up our own solutions. And in cases where the composer notated only a sketch, such as in the figured bass parts, decisions as to what notes to play fell once more on the performer, as intended.

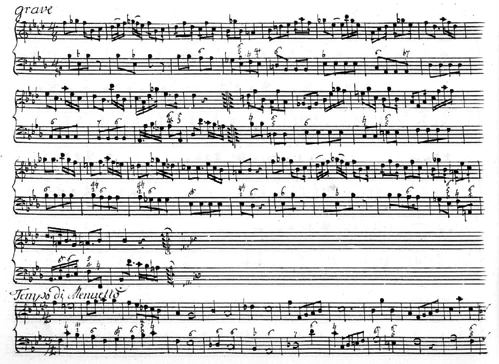

Quantz, Sonata [no. 20] a flauto traverso solo e cembalo,

Berlin, Staatsbibliothek, Mus.mus. 18020

(SPES, Monumenta Musicae Revocata, v.21)

Berlin, Staatsbibliothek, Mus.mus. 18020

(SPES, Monumenta Musicae Revocata, v.21)

Vester’s principle sounded refreshing: how could a performer make a more "independent" interpretation than to dispense with the editor altogether? But presenting early musical texts in modern notation presents problems of its own, and a proliferation of facsimile publishing that began in the late 1970s seemed to signal the liberation of these texts from the hands of even the most responsible and learned editors. Mark Meadow’s Musica Musica series produced inexpensive, spiral-bound editions of much of the most popular instrumental repertoire of the early 18th century, while his motto “Be authentic—play from facsimiles”, cheerfully announced the apparently simple connection between text and performance practice.

Not all facsimiles were as unsophisticated, however. High quality fascimile editions of early tutors began to appear from the publishing house of Minkoff in Geneva, Switzerland. And the early 18th-century repertoire of the flute was from the first a particular focus of Studio per Edizioni Scelte (Select Editions Workshop, often abbreviated S.P.E.S.) of Florence, Italy. Their luxurious editions came splendidly printed on fine paper and gorgeously bound, furnished with thoughtful and intelligent introductory essays. The great majority of the S.P.E.S. output, nearly 100 titles, consists of music for transverse flute. Two series are entirely dedicated to the flute: L’Art de la flûte traversière and Flauto Traversiere. Their repertoire, according to David Lasocki, Head of Reference Services at Indiana University’s Music Library and a noted scholar of 18th-century woodwinds, is "a stimulating mix of the familiar and the unfamiliar." The publications in the first series made available the classics of 18th-century French flute music: the suites of Hotteterre, Philidor, and de la Barre, as well as neoclassical works by Devienne, Delusse, and Hugot, most of them unpublished since their first editions.The Italian-titled series, dedicated to transverse flute works by 18th-century Italian composers, did the same for Locatelli, Platti, Tartini, Sammartini, Dôthel, and others less famous.

The Italian series had the additional merit of bringing these works to the attention of an early-music revival fixated on French composers and Bach. S.P.E.S. grew in 1978 from the efforts of four Italians who taught at the Verona Conservatory. In an interview in the German quarterly Tibia (14.3 [1989], 512-18), Marcello Castellani, recorder and traverso professor at Verona and general editor of the two transverse flute series, spoke of their goal: to provide baroque music students with a series of original works chosen according to a plan rather than for marketing reasons. They believed presenting these texts in their original appearance, whether printed or manuscript, to be a helpful way of fostering a relationship with a past era. And they were determined to keep their own interpretations of the musical text from appearing in the editions. "In all the series," says Lasocki, "the choice of sources to reproduce has been made with care and insight. It is wonderful, for example, that the Handel volume includes all the autograph manuscripts as well as both 'Roger' and Walsh prints, and that we have easy access to all surviving 18th-century manuscripts of Bach’s b minor sonata. To each volume Castellani, occasionally another scholar, contributes an interesting preface—alas, almost exclusively in Italian—covering the sources, style, and performance practices. The S.P.E.S. flute facsimiles represent the great unsung achievement in the early flute publishing world."

After studying English at Magdalene College, Cambridge and baroque flute at the Royal Conservatory in The Hague, Ardal Powell was a co-founder of Folkers & Powell, Makers of Historical Flutes. He received his Ph.D in music from Cambridge University in 2004 and is active as a performer, researcher and editor.